Salve alumni fight food inequality through science, local initiatives

With the pandemic beginning in 2020, researchers at Northwestern University found that food insecurity more than doubled during the economic crisis brought on by the outbreak. In 2021, Feeding America—the nation’s leading hunger-relief organization—estimated that around 42 million people, including 13 million children, are currently facing food insecurity. That’s about 12.5% of the U.S. population, which is the largest number in recent decades.

But the pandemic and its impact on food access are just one small part of a larger issue stemming from global warming and climate change. The United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) observed that climate change is already affecting food security through increasing temperatures, changing precipitation patterns and greater frequency of extreme events.

All of these issues add up to a growing concern around food inequality and food access—issues that impact every single one of the Critical Concerns of the Sisters of Mercy. This is where Salve Regina alumni are stepping up to offer solutions with the hope of combating these rising challenges in a variety of different ways—from researching plant science for healthier crops to helping maintain sustainable local food sources.

Becoming a Plant Scientist

According to Ricky Tegtmeier ’19, who graduated with a bachelor’s degree in biology, the talks around food access start at the macro level with how effective the world is at growing food. Originally from New York, Tegtmeier spent much of his time at Salve Regina doing research under Dr. Jameson Chace and Dr. Steven Symington, both professors of biology and biomedical sciences.

Tegtmeier also worked in the hydroponics lab. Hydroponics is a method of growing plants where the medium of growing is water instead of soil, but the water has the same spectrum of nutrients that plants would need in a normal soil environment.

“We adjust the pH of the water similar to how you’d adjust the pH of the soil, so it’s good living conditions for the plant, and then we put them under artiffcial light in a controlled environment,” Tegtmeier explained. “Then we have a very high degree of control of plant growth, and we can do very controlled plant experiments.”

Because of his experiences at Salve Regina—as well as working on small organic farms in New York’s Hudson Valley during the summer months—Tegtmeier knew he wanted to pursue a plant science position. Still, he wasn’t sure that he wanted to focus on plant breeding and genetics until the end of his undergraduate research internship with Cornell University. A fter that internship, he went on to study plant breeding and genetics in Cornell’s doctoral program.

Currently, Tegtmeier has two major components to his work at Cornell. One side of it is a statistical, bioinformatic, computational based project where he’s mapping new sources of gene resistance or susceptibility within the apple genome. The other part of his job is applying genome editing to knock out or turn off genes that are associated with disease susceptibility. Tree fruit breeding is tedious and long, and Tegtmeier is trying to find ways to help fruit trees resist a particularly destructive disease called fire blight, a common bacterial disease that can quickly ravage apple trees in a region much like a wild fire.

So how does this all fit into food access? For thousands of years, plant breeding and guiding the genetics of plants has been common practice to fit plants into environments. Once plant scientists have a certain disease-resistant plant variety that is good for a certain region, then growing and harvesting become more stable. Due to climate change, predicating how the climate is going to play out in a region is becoming harder, according to Tegtmeier.

“Every plant breeder looks about 10 years in the future, but if you have those widening margins and you’re breeding for 10 years in the future, then it’s harder to find the mark that will continue to feed eventually 10 billion people by 2050,” said Tegtmeier.

It’s clear that Tegtmeier’s task is essential in the grand scheme of food scarcity. But while plant genetics is a macro-level look at food access, more Salve Regina alumni are working at the local level to provide food to their communities.

Aquidneck Community Table

Crisis usually shows the holes in both global and local food supply chains, and the empty grocery stores during 2020 showed just how vulnerable people are to food shortages. That’s where more locally grown and harvested food can come in handy. Founded in 2016, Aquidneck Community Table (ACT) works to build a sustainable local food system through community gardens, farmers’ markets and public education initiatives in Newport and the surrounding communities.

Two Salve Regina alumni who work full-time at ACT are Kelsey Fitzgibbons ‘11 and Mary-Kate Kane ‘10, while Anjali Gordon ‘20 completed an 11-month service term at ACT through TerraCorps—the environmental branch of AmeriCorps—where she served as the sustainable agriculture coordinator.

“I think 2020 specifically really drove home the importance of having a local food system, especially during the pandemic when the shortages of different items were really being felt,” said Fitzgibbons, who majored in social work at Salve and is now the farmers’ market manager at ACT.

During the pandemic, Aquidneck Community Table saw a huge uptick at the farmers’ markets with people looking for goods that they would have otherwise found at the grocery store. ACT also saw a huge interest in gardening, as people turned to growing their own food.

“We all just felt such a lack of control over what was going on, and gardening was something productive that you could do,” said Kane, who was an international studies major while at Salve Regina. “You’re outside, breathing the fresh air, growing healthy food for yourself and your family.”

While Newport residents and those living on Aquidneck Island are considered to be well-off, that is not always the case. There is a huge community of people on the island who live in poverty or do not have access to good food, according to ACT.

“Even if people have access to food, it’s not always good, nutritious food that they can put in their body,” said Fitzgibbons. “So, they may be able to walk to the corner store … and get a bag of chips, but they might not have access to a grocery store where they can get cucumbers and carrots.”

Aquidneck Community Table has tried hard to fill in the needs that they see in the community—especially during COVID-19. In 2020, ACT was allowed to only have their employees in certain gardening spaces, so the team grew, harvested and gave away fresh food by donating it to various organizations. They also partnered with Rhode Island’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) so that customers could use SNAP benefits at the farmers’ markets, and they were able to coordinate with local Spanish speaking communities to give out grocery certificates for use specifically at the markets.

View this post on Instagram

During Gordon’s service term at ACT through TerraCorps, she grew and distributed lots of produce. Gordon also helped build a youth program called the Root Riders. The Root Riders gives teenagers between 14- and 17-years old the opportunity to gain job experience by riding across Aquidneck Island to community gardens, growing food, and learning about sustainable living and small business practices. The six-week program launched this summer 2021 and is a paid apprenticeship.

“Aquidneck Island is considered a food desert—mainly because we’re an island,” Gordon said. “I think that also touches upon the importance of community members learning to grow foods and vegetables …. Having youth involved in our mission is so important, and you do really see a different side of it all from their perspective.”

New Hampshire Food Bank

Maria Smith ’16 was an environmental studies major while at Salve Regina. Like Tegtmeier, she also grew plants in the hydroponics lab with Dr. Chace—and because of her experiences at Salve, she developed a real interest in working with local food. A fter college, Smith served for a year with AmeriCorps, working with a nonprofit in Massachusetts that trained new and refugee farmers. She then went on to work as a wholesale distributor at a large-scale organic farm in New Hampshire.

“When working with local food and trying to have them to move it—a lot of the time you’re just getting food to people who can afford it, and there’s a lot of stigma that all this great food can be really expensive. It’s hard for everyone to access,” said Smith. “So always on the back of my mind, there was a little voice saying, ‘We can do better.’ I was really interested in … moving toward food access and helping everyone get access to the nutritious food that they need.”

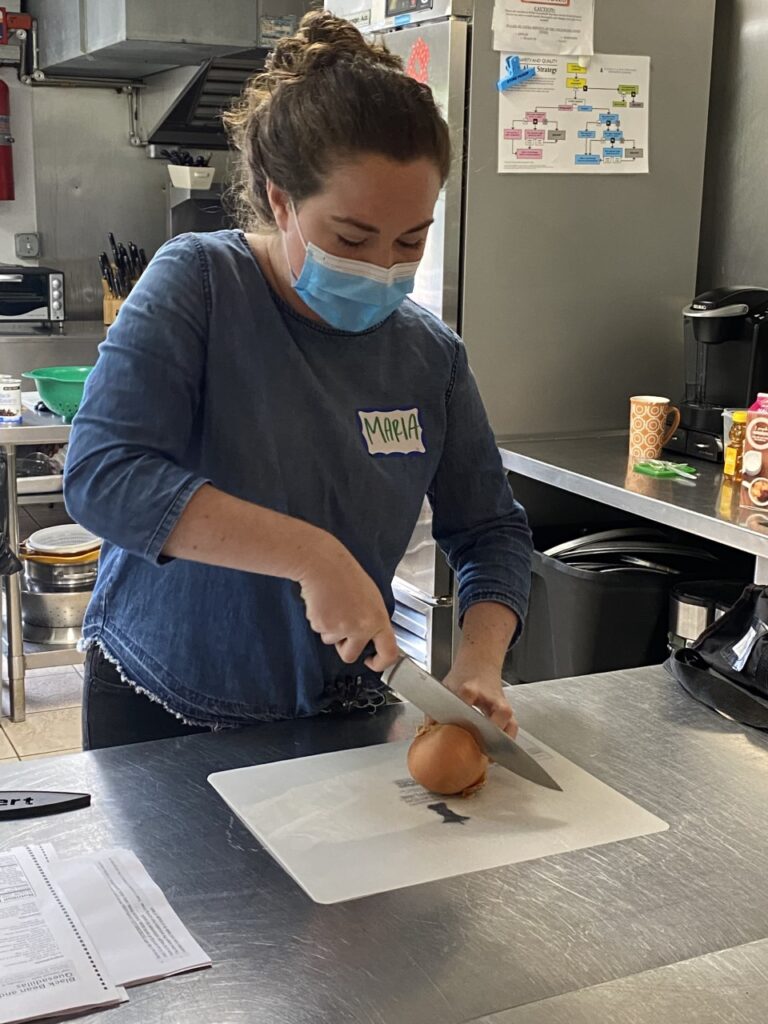

In the past, Maria Smith ’16 has worked with a nonprofit in Massachusetts to trained new and refugee farmers and as a wholesale distributor at a large-scale organic farm in New Hampshire.

In 2019, Smith started her job as the Cooking Matters NH program coordinator at the New Hampshire Food Bank. Food banks exist across America to help people with food access, and they also help alleviate food waste. Without food banks, individuals and families who are truly struggling might starve.

“Food banks … don’t necessarily give money to individuals,” Smith explained. “We work as kind of the warehouse or the distribution center that gets food to agencies like food pantries or soup kitchens. We’re kind of like the middleman.”

The New Hampshire Food Bank is the only food bank in the entire state. In 2020 during the pandemic, it distributed more than 17 million pounds of food and almost 15 million meals through its different programs, Smith shared. Smith saw firsthand how the need rose through 2020 across New Hampshire. The New Hampshire Food Bank started mobile food pantries that could travel across the state, and she helped distribute food at these mobile stations.

“Especially at the beginning, the lines were just so long, there were so many people coming to get food,” she said.

Even during the crisis, education around healthy food choices was crucial. An unhealthy diet can cause many lifelong issues and is linked to poor health and mental health outcomes. Cooking Matters is a national program in all 50 states with the goal of helping end childhood hunger by educating low-income families on how to shop for and prepare healthy meals. As the Cooking Matters NH program coordinator at the New Hampshire Food Bank, Smith’s role is to educate low-income families on cooking healthy, nutritious meals. Usually, these classes happen in person, although during COVID-19, she taught via Zoom.

Smith thinks it’s important to emphasize that families in need do not necessarily look like a stereotypical impoverished family, and that you can never really know who is struggling with putting food on the table.

“Even if someone has a house and if they have a job and they look like they’re doing okay, you never what’s going on,” she said. “It’s not necessarily a person in a homeless shelter. Anyone can be food insecure and need help …. If you’ve never done it before, it can be so hard to try to ask for help. We have people in the food pantry lines that have tears in their eyes because they never thought they would have to do this.”

Like Fitzgibbons, Gordon, Kane and Tegtmeier, Smith is passionate about carrying out Salve Regina’s Mercy mission by helping to provide food access to those who are vulnerable—whether it be through climate change, a pandemic, or personal struggle.

“When I do my work, I definitely feel like I’m living out the Mercy mission whenever I can in whatever way I can,” said Smith. “Just helping those who need it.”

This article was originally published in the “Report from Newport” Summer Issue 2020. There have been slight modifications to this article from its original form.

Salve Spotlights is a series of people-centered stories periodically featured on SALVEtoday. Check out the tag Salve Spotlights for more stories.